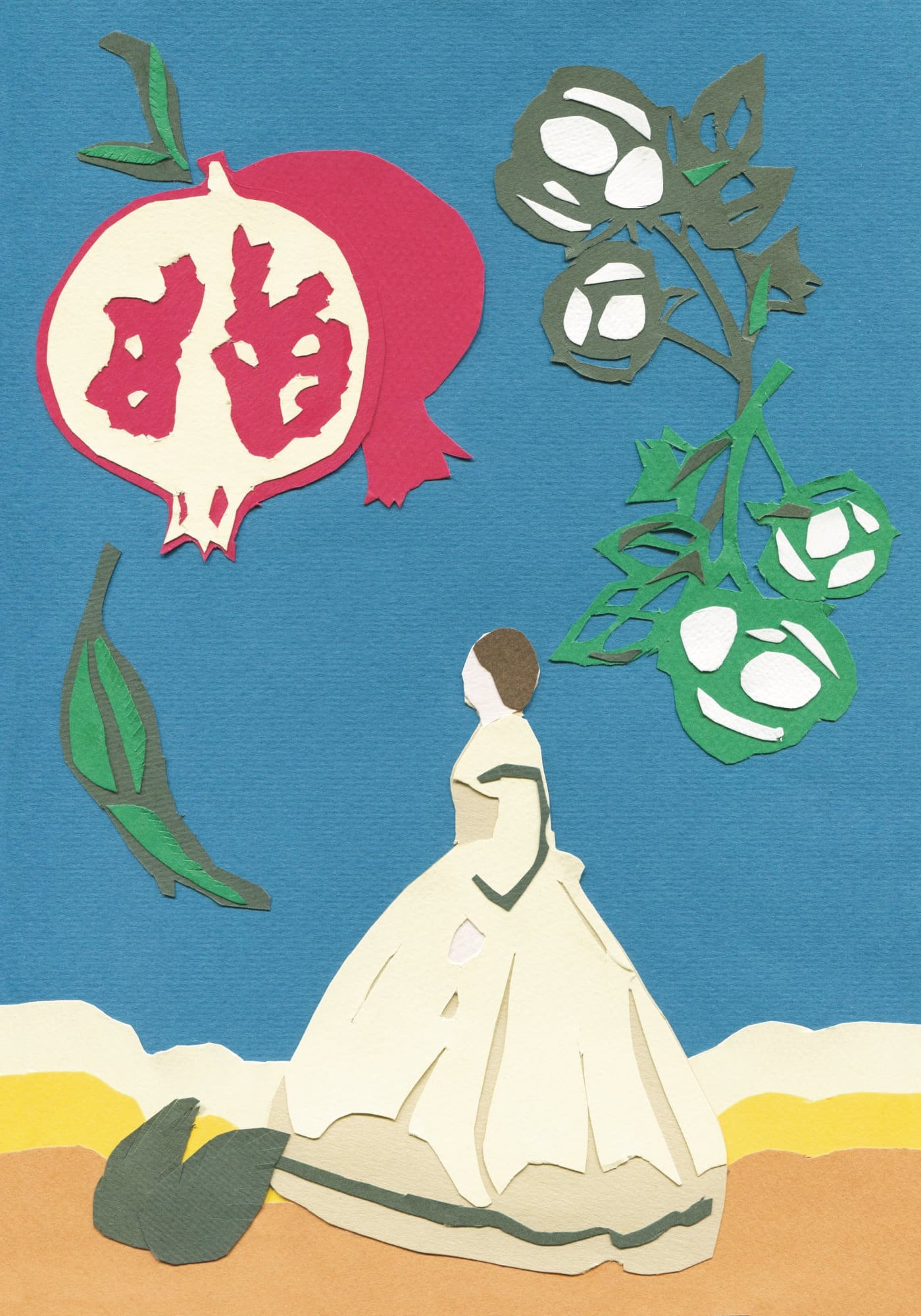

Françoise Rutland

21st of April 1826

At first, it is not apparent what has brought me back to the present moment. I find my gaze resting upon a laurel leaf embossed into the lower corner of the hall mirror, one glove still hanging limply in my hand, unnoticed. A sound came tugged at my mind again, and again. I gasp as if resurfacing for air but all I can hear is the sand blown against glass. I refocus, seeing greying hair, eyes creased, my dress sombre, and it takes me a moment to recognise myself, in the present, not the woman I was when I arrived at Mockbeggar Hall, twenty-four years ago.

And then it comes again, from below me and it’s Elizabeth. I hear the approaching carriage, the crunch of Rood’s hooves as it turns from the stables led round by Ewan.

Elizabeth, in her apron, pushes the door open and hands me my parasol. Her hand encounters mine and am caught by how much her misshapen fingers remind me of time passing. Perhaps she did not notice, though I know she has. I wonder how she feels to have spent her life like this, here, with me. I step out into the dun light, the yellow of the daffodils flattened. Clouds blow over and the open horizon will be there waiting for me, to merge with the flat silver blue of the sea, stretching west.

I feel a belonging as I admire the horse’s sweeping back, head held high. An arrogance, in the way he holds himself, swaggering and smelling of hay and leather. My horse, my carriage, and my people; my home. The day I acquired Rood was another triumph, another chink built. Marie Anne

will have her home always.

I tend to think of Marie Anne as my little girl despite being grown. We pick up the pace towards the village, the dogs lollop along as I plan today’s duties. My father’s congregation, Rev. Thomas Danneth, and his many charitable organisations run by the haggard and overstretched in Liverpool, waiting to spill their grievances. Father has been dead years and I inherited the duties along with Mockbeggar, one duty in exchange for the other. I was not meant to be still involved with the parish. He, and I, had foreseen a different life, in exotic climes. Funny how things turn out.

Years ago, as the sunset in a blaze of peach, and red across a bruised sky, I arrived at Mockbeggar Hall. I left Peover Hall behind, taking only Ewan, then still young, and Elisabeth who was always mine. Ewan’s natural discretion and palpable loneliness of the displaced resonated with my predicament. Secluded deep into the Lancashire countryside it was a landscape I knew I did not belong to, with a husband often abroad, and an infant child, I found myself gravitate towards the stables and I knew to trust Ewan to keep his nerve.

My husband, Louis William Boode, was rarely at Peover Hall. Marie Anne, our daughter, appears to have no recollection of him. His trips to the family estate, the Greenwich Plantation, across the ocean to Demerara kept him away most of the year. The six weeks it took The Boode to arrive somehow seemed to not only leave us behind but erase us completely. I knew not to expect his letters. It was only after I left Peover that they started arriving, first sent to St John’s parish in Liverpool then at Mockbeggar after the shipwreck. We dragged the sailors out of the squalling seas onto Leasowe bay and the captain felt compelled to publish his gratitude in the papers. Good intentions I suppose. Letters sealed with the Boode insignia alternating between reason, and pleading, demanding, and bargaining. I stopped opening them and Ewan knows to keep them safe at the gate lodge.

I slip into recollection as the carriage slows and steers right, uphill through the village, weaving through people on foot going about their routine business. Despite the dry weather the dark sandstone still looks dank. Rood’s rhythmic clipped footing adjusts as his hooves sink and grip. He snorts uphill passing beneath the Tudor tower, towards the overhanging small holdings towards Wallasey docks.

Oak trees line the road where cotton merchants’ homes impose, Millthwaite Hall above, a befitting monument to modern times. Labourers, in their heavy linen clothes, swarm the roads, gusts of dust rising in a permanent haze above the quarry on Moss View cliffs. A grinding of red ripping through woods past the boys’ school, disturbed ground, yielding bits of green metal, worn carvings of pagan gods from northern warriors obliterated, and unearthed for the amusement of dishevelled schoolboys.

My dogs growl and snap, there is a lot they do not recognise. The red sand slides and rises beneath the wheels of carriages and labouring carts. Ewan’s steady hands at the reigns reassure me but animals sense inexorable change. My mind is again drawn to Marie Anne, her future. The farm dogs jittery, in packs, their ribs clearly exposed beneath mangy skin, band together for whatever sustenance they find. They are kicked away from beneath cartwheels which clog the two roads leading through the village.

Despite the open fields and marshlands of Mosslands the road feels cramped. Abandoned farm walls look incongruous, air dusty and black from furnaces of freighters ahead. The clanging of wharfs and cranes resonate in conflict with the din of stonemasons and quarry.

I hope not to spot The Boode yet struggle to look away. I hide into the canopy and scan the quays. I need to see that the freighter is absent, as if that was reassurance that my secret was any less real. Moored with the stench of brine-soaked tar and teak, muffling dust rising off these floating vessels as they unload ubiquitous cargos of cotton, sugar, and tobacco. Holds saturated in fear, and betrayal.

My pounding heart slows, only past the wharfs. The heart nurtures its fears twenty years in. Cobbles and tram lines leading down the riverbank past cramped workers’ cottages, the breeze gusting away public house fug, ringing with hollers, the carriage clatters on.

Ewan helps me down. The estuary opens towards my beach and ocean, cluttered with vessels and skiffs. Passengers crowd in, and he, imagining I am the girl of twenty-three I was, wants to accompany me. He can return to Mockbeggar with Rood, see to the dogs and gardens. I’m glad to be crossing alone.

The steamer is clearly visible, departing Liverpool, pulling against the tide towards Woodside. Office clerks alighting from tram and train to and from Hamilton Square. My mind fixes on a seagull as I wait, my breath deepens. Now that I am me, nobody’s mother, daughter, sister, or wife.

Wife – I came to Mockbeggar with Marie Anne in my arms, Elisabeth and Ewan. Otherwise alone. Peover distant enough for a connection not to be made. The sand-duned coast was sparsely inhabited while the affluent relocated from disparate regions in this newly enlightened era. It was October, and I suppose my grief drove me to choose darker gowns. The lack of apparent husband led people to assume widowhood. I did not disillusion them; I was a widow in all other ways. The captain’s published letter of gratitude turned assumption to fact.

Rev. Thomas Dannett moved with the great and good of the city. My father held wealth of his own when he entered the clergy. Backed by connections Rev. Thomas had few obstructions in securing the rectorship at St John’s, Haymarket.

As a girl I observed in awe the misery of many. As the years passed my schooling became less necessary, while charitable work was befitting a clergyman’s daughter. I started accompanying him and was kept writing letters for backing to lords, and merchants thriving in the regions as far as Eastham and Warrington.

Unlike my sister Phoebe I had no interest in being indoors. She was older and gladly groomed for a socially improving marriage. Once of age she seemed to have lost all interest in anything else. She kept my mother busy with events, dressmakers, haberdasheries, and such engagements. There was one aim in their lives, and they got on perfectly well without me.

Yet I brought an end to Phoebe’s marriage endeavours and my girlhood. One day over supper, my father and I discussed the day’s concerns. He mentioned a reverend in charge of St John’s parish in Jamestown, Demerara who had written. Placenames familiar from every emblazoned every cargo arriving at dock, yet ignorant of the implications.

I was intrigued by a change from the daily hopeless drudge that we struggled with at Haymarket and thus we received the wealthy Dutch gentlemen into Liverpool society, who owned plantations in Demerara. This was an exciting change, and social letters of acceptance flowed back.

By the time the gentlemen Louis Wilhelm and Andreas Christian Boode turned up for tea the novelty had passed. Louis started visiting us regularly following Phoebe and Andrea’s marriage. His fair hair, pale blue eyes, and strong jaw provided a foil to his Dutch lilt, and I fell in love with the little I knew of him. Perhaps predictably we followed in my sister’s footsteps down the aisle a year later.

Once Marie Anne was born, he would return to Peover Hall, weather-worn from the sea voyage from Demerara, aromas of teak and tar accompanying his taciturn demeanour. I wondered if, had I given him a boy, life would have been different. It was when he asked for a divorce to remarry the heiress Sarah Pascoe that I packed and left for Lancashire, to Mockbeggar.

As I return now from Liverpool, sun setting ablaze, I feel my heart rise. Marie Anne is grown up and safely at court with a devoted husband. No need for my protection, her legacy secure. Perhaps it is time for freedom, and letting Louis go. As the ferry Peony progresses across the retreating tide, years slip off with each step towards Ewan. I would be answerable to nobody, at liberty to pursue who I wished. I met Ewan’s eyes as he took my hand onto the carriage.

“When we get home, Ewan please bring me that chest of letters. It is time.” I said.

“As you wish Margaret.” His tone neutral, yet the smile apparent as we set off towards our home, Mockbeggar Hall.

As I return now from Liverpool, sun setting ablaze, I feel my heart rise. Marie Anne is grown up and safely at court with a devoted husband. No need for my protection, her legacy secure.

21st April 1827

I stand squinting in the chill sunshine picking sharp patterns off the new monument, sun setting behind us. Beautifully gothic, local red sandstone, my mother would have approved.

Mrs Margaret Boode of Leasowe Castle, was killed by a fall from her pony carriage on the 21st of April 1826.

It has been a year since my beloved mother travelled down this village road. The dogs still roam, and the sand still rises from beneath steel-shod hooves. Curs like the one that got beneath my mother’s carriage that evening still roam. Its screams upset Rood who took off tipping the carriage. Ewan suffered a broken shoulder, my mother never recovered from her head wound.

Nine days later my father remarried the plantation heiress Sarah Prescod Clarke in Paris, relocating to Georgetown.

Our young daughter will never meet my mother. The works Margaret foresaw for Mockbeggar have progressed. I sometimes fancy her standing in the orangery, looking out onto the golden dunes, blustering, and flattening in turns, held in place by hoary marram grasses, with approval. The weather is endlessly changing, the sunsets breath taking. Ewan, like the hall, holds her memory, bound by love, and grief. Elisabeth moved back to her many grandchildren.

Note: Marie Anne Cust (Boode) sailed widely collecting rare flora and fauna, now in national collections, under the patronage of William VI. She bred Turkish Angora cats and horses. Aleen Isabel Cust, Margaret’s great granddaughter, became Britain’s first female veterinarian in 1922, a hundred years from now. Pomegranates still blossom at Mockbeggar Hall.